Wicked reggae duo Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare

met with FCJ in June for an interview at the SF Independent.

Photos by Luke Thomas

By Shivu Rao

July 19, 2009

It is oft said of meeting one’s heroes in person that it is sometimes better not to, for fear of encountering personal disappointment. In this particular instance, however, the opposite conclusion was reached.

When the Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakepeare tour roared through San Francisco last month, FCJ was graciously granted access to the famous and prolific rhythm section and production team. We met up with the famous duo before they headlined a packed-out show to a roomful of ardent supporters of Reggae music at the infamous Independent.

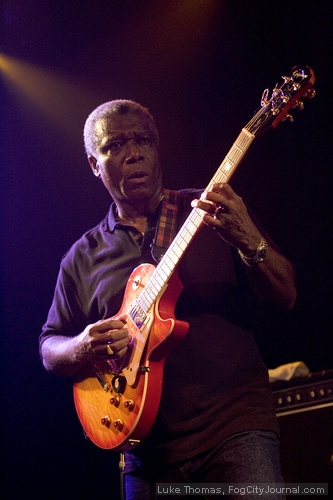

Robbie Shakespeare

Sly Dunbar

We found the ‘Riddim Twins’ in their dressing room in a relaxed mood after their afternoon sound check. They were ready to share their accumulated wisdom and anecdotes on a wide range of topics, ready to walk down memory lane and to explain the personal and technical rigors of being professionals at the top of their game. All this was done in a friendly and jovial atmosphere, setting the stage for an in-depth conversation that shed light on topics that will be of interest to musicians, music fans, Reggae lovers and music historians. We hope the interview will be appreciated in a similar vein of the warmth and respect that the interview was conducted with.

Meeting Sly after the sound check, we launched directly into the topic of various rhythm driven music, such as Latin American, African and Indian music. This seems an appropriate place to begin when talking to one of the worlds most recorded drummers.

Shivu Rao with Sly Dunbar in the “Green Room” at the Independent.

FCJ: How influenced is your playing by non Western music from Africa, Latin America and India for example?

SD: When I started playing drums, the first thing that I saw was Africa, right. As a kid growing up in Jamaica, I would hear these kinds of rhythms. Now I’m into the Mediterranean, Arabian and Indian types of stuff. And of course, African and Brazilian stuff, too. What I wanted to do was to bring some of those elements to Reggae, which I think has happened. But there’s more to do than what we have done so far. The drums are where the real soul is and there are lots of people around the world playing drums. The drums are the heart, the template where everything goes around it. I’m trying to relate this idea that in every culture in the world, the drums project the culture. You could take a spoon and beat on that and that’s a drum (laughter). Drums mean a lot to me. When I hear anybody play the drums, I can relate to that, anybody…

FCJ: Its a language for you?

SD: Yeah, its a language. I don’t see myself as a great drummer, but I’ll think of things and do it. I don’t go by the rules. It’s a lot of work to go by the rules so I prefer to break the rules and create my own stuff. I create by listening to people and I try to hear the drums and I go for that sound. When I go for that sound, I try to get the spirit of it. For example, a bass part will give me an idea for a rhythm and that’s how I go about creating things. I don’t go the route that everybody goes through because I think that route is very hard (laughter).

FCJ: Okay. So its more instinctual and organic for you?

SD: Yeah. So I try to go about and create my own style and approach. When I started doing that in Jamaica, and it started happening, people would start coming up to me for what I was offering. So I try and create and build on all the previous ideas and build and build until where that sound and approach became the norm for a lot of Reggae music. I was thinking of what kind of part I could play in Reggae music, and so I said I would like to create a style of playing where the world would say, ‘this is the sound of Reggae music, and we have to play this.’ And it looks like it has worked (laughter).

FCJ: It has worked, I can imagine for a lot of young kids who wanted to play Reggae drums, your playing was the first thing they heard.

SD: I wanted to play more than a basic Reggae beat and that was my goal. You have to go beyond that, take various ideas and flip it to the drums. We were talking about the power of the drums. Sometimes I sit and think about what the drums mean to different people, like after a concert, people come up and say, ‘you don’t miss a beat and it was constantly in your face.’ I say well, as the drummer, I supply the template and keep the beat and lock it where everybody can go around me. I have to keep it firm and steady so the people there can feel something rocking, you know.

Sly Dunbar

FCJ: Definitely. I wanted to talk about your early days in Kingston at Trenchtown Comprehensive High School. What was your musical exposure in those days, in what form did it take?

SD: Yeah. It started even earlier than when I got to Trenchtown Comprehensive High School. My mother used to work at the Kingston Airport so she would come and tell me about the foreign artists that were coming in from America. In the early days, there would be a parade and we would see these artists passing in the street. And we used to live in East Kingston and they would pass my street. I used to be able to remember the melody of songs really well. But when you are a kid, you want to be a fireman, you want to be a cricketer. When I started to listen to the Skatalites, you know, Llyod Knibbs, and listen to all the R and B coming out, I said, ‘wow!’ A friend of ours had a club in the neighborhood. We would go there on Friday nights and we would dance and listen to music and go to parties and things like that. That’s when I was listening to Sly and the Family Stone, Motown and Stax. The beat was everything you know. All our friends would sit and gather and dig the music. At the same time there was a concert at Trenchtown Comprehensive when I was fifteen, where Ken Boothe came to the school and performed. I decided, yeah man, this is what I want to do, you know. I used to take my lunch money and go to the jukebox and punch it out on the box and listen to the all the songs and later walk it home (laughter).

FCJ: So one day you decided to become a musician?

SD: Well I remember when I left school at fifteen, I was supposed to go to Kingston College. A friend of mine came by with a two-track tape recorder and left it with me. Lloyd Parks, a bass player and me would write songs and sing them onto the tape recorder. At an early age I could listen back to what we were doing and know exactly how it would sound. Lloyd would come around every day for two years, we would be under the mango tree in my yard, making music, me and Lloyd Parks. This is where the whole thing got out of hand. I remember playing in my first band, the Yardbrooms. The first song I played on was a song called ‘Red Red Wine,’ Reggae version. When I moved on from there, a friend of mine, Ranchie McLean, was in a band. Their drummer had left and gone, so they said I should play drums, so I started playing. Ansell Collins was on the keyboards and liked my playing. I was only around fifteen but I had been listening to a lot of music so I could hear and know the snare drum parts and the other parts. So then Ansell Collins asked me to come and record on a song called ‘Night Doctor,’ and it came out as an Upsetters release and it was a big hit. Ansell was the one who produced it and I think he sold it to Lee Perry. Later that year, I did some more recording, nothing big. And then the big hit came, it was called ‘Double Barrel.’ I was sixteen years old at that time. Ansell asked me to listen to the piano parts and we kind of came up with the bass line and intro to the song and what everybody else should play. So me and him stayed back after rehearsal with the band and worked the song out together for a week. I told them its going to be a million seller and they laughed at me. And it was! (laughter).

FCJ: So at this point you considered yourself a professional?

SD: No I didn’t consider myself a professional because I was using what I had heard on records. And studying a lot about how to make a record and how to put a song together. And also learning from what we heard on the radio. We cut the ‘Double Barrel’ at Dynamic Sound Studios and we worked with a guy called Linford Anderson who recorded the session.

FCJ: So you were one of the in-demand drummers at that time?

SD: Not yet. I was still trying to prove my point. Because there were a lot of good drummers in Jamaica at that time.

FCJ: People like Lloyd ‘Thin Leg’ Adams.

SD: Yeah, Thin Leg was good. There was also Winston Grennan, Leroy ‘Horsemouth’ Wallace, Santa Davis, Mikey ‘Boo’ Richards, Paul Douglas who plays for Toots and the Maytals now. Phil Callender, who used to play at Studio One. All these guys. At that time a lot of Reggae drumming sounded similar, so I figured I’d have to come and do something different. Another friend of mine owned a discotheque and we used to go there nights and listen to foreign songs. And I thought if I could get the drum sound to sound like a foreign record, it would make a big difference. Because the drums in Jamaica at the time sounded the same. At around this time there was a little session going on at Channel One Studio. I met Ernest Hoo Kim who was the engineer down there and I was telling him about the drum sound I was trying to get. So he said ‘okay’ and we took two years to get to the sound. We were listening a lot to the ‘Philadelphia Sound.’ I thought that drum sound would do good in Reggae. If we could get that sound, it would be great. We worked hard on it and actually got something.

FCJ: So it was a combination of the studio and the drums working together to get the sound?

SD: Yeah. It was a very good room and they had a very good soundboard, an API recording console. Still recording on four track, but API was a high-end recording console. What pulled it all out of the nutshell was when we got some free studio time – because all of us had no money – we recorded five songs by four musicians. One for each musician and one for the engineer as payment for the studio time. So I made a song for Ernest Hoo Kim called ‘When The Right Time Come’ (1976) and I gave him the rhythm track and said, ‘that’s yours.’ This was when I was trying to change the whole thing by playing a pattern right through the song on the rimshot, instead of the one drop beat. The song became a big hit and everybody took notice of the drum track. The way I played the track, a lot of people thought there was a delay effect used on the console. But they realized that I was actually playing it. So everybody was curious to get the same kind of thing. Because once you have a hit record in Jamaica, everybody wants the same thing. Joseph ‘Jo Jo’ Hoo Kim (brother of Ernest) then allowed me the freedom to come to the studio and create a whole lot of patterns. They would take the time with me to develop the patterns and the songs for me to play. That was what really stood out for me. From there it filtered out and a lot of people started asking me to play because they liked what they heard.

FCJ: So you became a ‘beat engineer’ for the genre of Reggae at the time and later on you released a CD of 843 different drum patterns called ‘Reggae Drumsplash.’ Did you start cataloging the beats at an early age or how did you do that?

SD: Well, I just remembered them or listened back to one of my older records. I wasn’t thinking of making a CD then, I was just making beats. Just like how James Brown and rhythm and blues had different drum beats for different songs, I thought we could do the same for Reggae music to give it a flow. So I started variating from the one drop and get a riff. So it opened up different grooves.

FCJ: It opens up the other musicians too.

SD: Yeah. And so that’s how it went. You’d listen to a song with a singer and you try to fit the beat with the singing. Good drummers will find a beat that will match the song. I came with that approach even before I started recording. I learned a lot of that approach from Lloyd Knibbs (laughter).

FCJ: He had already mapped it out?

SD: Yeah man, he had mapped it out. He had a song called ‘Addis Ababa’ and he played a steady pattern through it and he wasn’t playing the one drop, he wasn’t playing the regular thing. This is the genius where I got the inspiration from to go through and kind of break it up, you know. Also I grew up listening to rhythm and blues, Motown, rock and roll, so that had its influence too.

FCJ: So how did you experience the other types of music, on the radio?

SD: Yeah on the radio. And there were a lot of discotheques in Jamaica at the time. We had a friend who owned a discotheque and we used to go there on Wednesday nights and sit down to listen to the music. I remember a song we used to listen to called ‘Love Jones’ (sings the chorus of the song by Brighter Side of Darkness) and there was a drum roll on the tom toms and I used to go mad for that roll (laughter). This is why I use four tom toms. Because when you have four toms, you don’t have to play a lot, with different tunings, you can play simple things and it would sound good. When you have two toms you tend to play too much to make it come over. Also with four toms you can get the stereo panning effect, and that’s what I can hear in my head. Basically when you sit at the drums, you have to be thinking about what the producer wants to hear as well as your audience and you start focusing on what the sound will be like on the recording even before you play. So I come up with drum rolls that get across on the song.

FCJ: So you’re already hearing the end product before you play it.

SD: Yeah, yeah (laughter).

FCJ: Since you and Robbie have played so many genres, how do you adapt your style?

SD: It’s easy, just listen to the song. When the singer starts singing, you hear the tempo and the patterns coming together. You not only play the song but you perform the song with the singer. So you try to get inside the song. If you know the song inside out, you can flawlessly map the song. For example, on ‘Private Life’ with Grace Jones, you’d sit there in the rehearsal studio and map out the roll placement and the approach to the feel of the song. So you set it up where can almost feel the roll coming up when you reach that part of the song, along with the attack of the playing.

FCJ : So you have a mental map of the song from all angles aside from the sound itself?

SD: Yeah, you have to capture the realness of the track, what people who buy the record might feel.

FCJ: When you’re playing a song, it’s easy for a lot of people to overplay or underplay on it.

SD: I always think of playing steady, solid. So people hearing it will hear that quality in it. And if the singer goes to chorus, you can move to the tom toms for a change and then after come back in with that steady beat to give it a flavor. So it’s all strictly rhythms, and this is what I get from African and Indian stuff.

FCJ: Okay. I wanted to discuss some of the more famous recordings you’ve been on. For example, Peter Tosh’s ‘Equal Rights’ album.

SD: Yeah that’s the first album we played with Peter. Peter did not want any straight 4/4 beats on it (laughter). Everything had to be one drop. So I had to play around with that. I think it’s a wicked album. There’s a track on it called ‘Stepping Razor’…

FCJ: Fantastic song.

SD: (Laughter) Robbie said that certain drum fills on it were crazy. He liked it. That was recorded at Randy’s Studio. Some recording sessions it depends on how comfortable you feel. You can do a lot of things. The next day, you might not feel as comfortable as you did and you wont be able to do the same things in the same way or get the same sound.

FCJ: Up and down.

SD: Yeah. There’s an album that I think it is good, its a Serge Gainsbourg record we did in 1979 called ‘Aux Armes Et Cetera.’

FCJ: You guys played on that. And you toured with him too. What was that like.. French music with a Reggae band?

SD: Yeah, he was singing and we were playing Reggae. You think how will it work? But it works. Listen to the guy singing. It’s one of the wickedest Reggae albums, in my top ten for Reggae albums. There are no overdubs and its raw and six people playing at once going down. Usually when I do something, I want to move on to the next one. But that record, I listened to it and thought it was good. Usually I don’t get back and listen to all the stuff I’ve done.

FCJ: Tell us about some of the work you did with Grace Jones in the early 1980s. It seemed to push you guys out there in terms of recognition.

SD: Yeah, that really did. At first we didn’t know what were going to play. In one room you had one African, one Englishman, and the rest were Jamaicans in Compass Point, Nassau. Chris Blackwell wanted a kind of Reggae that would fit globally. Because we used to listen to so many records like Stevie Wonder and Earth, Wind and Fire, so we had an ear for the commercial attitude it would take. Take the sound from Jamaica and bring it forward. The first song that was cut on the session was ‘Warm Leatherette’ and the second one was ‘Private Life.’ I think its one of the best tunes. When I sat and listened to it, I couldn’t believe how it all sounded. Alex Sadkin, the engineer got this sound which was incredible. A lot of people think that was electronic drums, but its acoustic.

FCJ: It added to your global fan base.

SD: Yeah, no matter who we have played with, the Rolling Stones, Joe Cocker, Bob Dylan, Simply Red, Gwen Guthrie, they have their own fan base. But when they see Sly and Robbie on the credits, some of them will check us out as a result.

FCJ: What current projects are you and Robbie working on?

SD: As a follow up to ‘Reggae Drumsplash,’ Robbie and I are working on a virtual drummer program for Nuendo (a digital music workstation) where you can take drums and bass samples and move elements of it around. The bass and snare can be moved around. I’m supposed to send in some drum machine stuff, some dancehall stuff for them. Different elements of dancehall that you can use in the recording process.

FCJ: You mentioned you are still using electronic drums, like Syndrums.

SD: I use it mainly for the Taxi sound.

FCJ: Tell us how Taxi came about.

SD: Well Robbie and I figured we want a more direct approach in terms of bringing the music to the people and also owning our own product and production. You ask yourself, after playing all these sessions, where you may not own your own material, what is next? So Taxi was to answer that question. Rolling Stones, Bob Marley all these guys have their own distinctive sound. So we hope that when you hear Taxi, people know that’s the Taxi sound. This is what we are trying to drive to the people, that sound.

FCJ: Which do you prefer, acoustic or electronic drums?

SD: Well, last year time we toured Europe I used my electronic kit. I did not bring it to America this time. They both have their uses, but I prefer the acoustic kit, its more organic.

FCJ: What do you think of today’s Jamaican music?

SD: Its cool you know, but I think they could benefit more by going back and listening to some of the older stuff, just in the way that some of the earlier stuff had a a solid lock in the way the groove was played. Because if you don’t have that, it wont work. Sometimes there is an emotional side of certain things. That emotion is the groove. Especially playing live, the groove is so important, because its all happening at once.

FCJ: They are using more tools today, maybe not playing instruments so much. They want the music to come about fast.

SD: Yeah, they came up in the electronic and technology era where they build up around it. We came up in the manual era where you have to actually do it. When you had to play steady, there was no click track (Laughter). We knew it would take a bit of time to get there. And there’s a saying, ‘If you don’t know where you come from, you don’t know where you are going,’ you know? I always go back and listen to Motown and am still inspired by it. I was listening to Diana Ross last night actually (laughter).

FCJ: What do you think of music schools in general?

SD: Music school is important. But being a street musician, playing live a lot allows you to know whats really out there and what the people are up to. I was reading a thing on the Philadelphia scene and those guys, Earl Young and Norman Harrison, were street musicians playing at a lot of parties, so they knew what’s going on. So when they went to the studio, they could approach it a certain way and bring a certain groove which was real, like a song like ‘Mrs. Jones.’

FCJ: So this tour, you are projecting yourself as the main element of the show?

SD: Yeah, that what we want to do. Having a singer is fine, but we want the music to be the thing. I hope young musicians will do that too, where they go out and play as a unit and have the music as the main thing, rather than being a sideman to a singer all the time. The success of Booker T and MGs is a model.

FCJ: On that note, Sly many thanks for taking the time to talk to us.

SD: Yeah, man. Thank you for taking the time. I honor every interview. It means a lot to me because when twenty or forty people read the interview, some of them might be interested to check out the music. Every little step of the way it helps.

FCJ: It was entirely our pleasure.

—

We meet Robbie while he is snacking on fruit in his backstage dressing room, feeling relaxed and ready for the night’s performance. The interview has a special significance due to the fact that he admits that interviews are not his favorite pastime. We are thankful for the opportunity.

Shivu with Robbie Shakespeare.

FCJ: Robbie, thank you for taking the time to talk to us.

RS: Yeah, no problem, man. No problem.

FCJ: You’re touring the States, what is the musical emphasis on this time? A dub style?

RS: The emphasis is on Sly and Robbie style of play, not pure dub, but we do a lot of dub.

FCJ: So the emphasis is on your original material?

RS: Not necessarily, we just play the music that we like. A lot of people probably never get the chance to hear music like that you know. So we aren’t really playing a lot of our compositions. A few of them, yes.

FCJ: So what’s the oldest Sly and Robbie material you will playing on the tour, Taxi era stuff?

RS: Were playing some stuff that’s older than the Taxi days as well as some Taxi songs too.

FCJ: Going back to the beginning, where were you born?

RS: Eastern Kingston, Jamaica.

FCJ: So how did your relationship with playing music begin? Was bass your first instrument?

RS: Actually, when I was going to school, I used to love drums. Every kid in Jamaica loves the drums, you know. When you have two sticks in your hand, you can make a lot of noise. And later piano then guitar. After seeing Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett (Bob Marley and the Wailers bassist) play the bass, I started the bass.

FCJ: So music was part of the education in school?

RS: Yeah. I learned to read and write music in school. That was part of schoolwork.

FCJ: Okay. What was the name of the school?

RS: Vauxhall Junior Secondary.

FCJ: So you must have been around 12 or 13?

RS: I’m not very good with remembering time and dates (laughter). Cant remember them. I can give you approximately, I cant pinpoint it. Sly is good at things like that though.

FCJ: (Laughter) Okay.

RS: I don’t know where they got me from (laughter). Sometimes I cant remember where we played last night,or where were going tomorrow.

FCJ: You have played a lot of shows. You have done a lot of different styles of music. How do you adapt the styles and settle on the essence of the groove? For instance, in Reggae the emphasis is on the two and the four and in rock is on the one and the three.

RS: You know better than me, the mathematics (laughter). I just go with how I feel. If were working with a singer, once the singer starts singing, I just fit myself and make myself a part of it. Not trying to play over him or under him or be outside of it. I try for the right part of whats going on. And I guess Sly does the same thing too. When you’re recording with an artist, you can’t overplay or underplay. You have to be the right part of the foundation to work up from, you know.

FCJ: Does that feeling come from playing the amount of music you have played? Its not clear to anyone who tends to overplay or underplay. Whats the secret to getting it just so?

RS: When I was coming up, I used to like playing in club bands. And doing that, you need to keep the patrons and dance floor going for about an hour or hour and a half. And we still would have to play Top Ten songs, which may not be strictly Reggae music. Could be calypso, funk or soul, because Jamaicans loved a lot of that, sometimes more than their own music in that time, you know.

FCJ: In that time.

RS: Yeah. So you’ve got to balance it, so I guess it came from there. Plus, at parties and on the radio, they used to play a lot of funk and soul. The rock and roll part came from radio like Rediffusion (a defunct British radio network that served many colonial markets). I used to love listening to that as well as short wave and long wave radio or even AM transistor radio where you could pick up a lot of foreign stations. I used to hear a lot of that, you know.

FCJ: I read an interview with you where you said you really went for the Stax and Motown house bands, James Jamerson and those guys.

RS: Well, we grew up on that.

FCJ: So that stuff still holds you? Even now?

RS: Yes, even now. To this day. But you see we listened to all different types of music, you know, because not Reggae alone or neither funk or soul or rap or house is alone, you know? Its all music. I was in Morocco the other day and I heard some music and I said ‘wow, that’s wicked!’ you know (laughter). So you can get elements from that too and it can add a little. Because no music is say, ‘this is my original music.’ Everything is a relative of everything.

FCJ: Seen. You built the road as you walked along?

RS: Yeah, yeah. That’s what you do! (laughter). You try and clear a path as you go along.

FCJ: Tell us the influence of Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett (Bob Marley and the Wailers bassist).

RS: Well…what can I say? He is the man (laughter). Just the way the man plays the bass, you know. There are gun fighters and there are gun fighters, seen? I can’t tell you nothing more. He is a master for me. I have had help and influences from other people, but I have to give it mostly to Family Man. When you say ‘help!’ someone shows up. He was the one, as well as another man, a producer named Bunny Lee. They took the time out and made sure I was on the right track. I couldn’t be in my bed sleeping when Family Man was there, because he’d say “Ay, get up, get up. You said you want to learn. Come!”

FCJ: So he was right there and he passed it along?

RS: Yeah man, he kept me on my toes. I can’t thank him enough. No matter how great anybody will say I am, I know I owe it all to him. He took me under his wing, like I was his little son and even apart from music. If I got out of hand, he’d say “Ay, ay, ay!” to put me back on the right track. A whole heap of respect to him, you know.

FCJ: Seen. Was Carly around as well? (Family Man’s brother Carlton Barrett, Bob Marley and the Wailers drummer)

RS: Yes, Carly was around too. Carly was the man who used to say, “Robbie, come to the studio!” Sometimes I had to carry his drums, you know. I would go into the to studio with him and set up his drums. After setting up his drums, the producer would not let me stay so I’d have to go back outside and stand in the sun and wait for hours for him to finish and go look for a taxicab to carry his drums home. Carly was my friend, too, you know.

FCJ: And this was at what studios? Dynamic Sound Studio?

RS: Yeah at Dynamic Sound, I could not stay…(laughter). While they were working, I could not stay in there.

FCJ: You guys were very active during the Channel One (studio) period, too. Talk about those days.

RS: Yeah, yeah. When Channel One just opened up, I went there to play as ‘The Aggrovators.’ And then after, along the line Sly, Ranchie McLean, Dougie Bryan and Lloyd Parks started working with Ernest Hoo Kim, who was an engineer who owned Channel One studio. I came in after, and I was playing piano when I came in (laughter) and then guitar and then eventually bass, you know. Most of the bass played at that time was played by Ranchie, who is a guitarist. And I was playing guitar. He said he liked bass. I can play guitar but the bass is my first love still. Eventually we switched around.

FCJ: Can you tell us about how you and Sly got to be locked in step into the music together?

RS: More than one step (laughter). Yeah, with Sly thing, I used to play in the same band with Bernard ‘Touter’ Harvey (Inner Circle). I was playing at club named ‘Evil People’ because the original house band which was Fab Five had left. Before even that, I used to go to ‘Stables’ (Nightclub) and check out Ansell Collins and Lloyd Parks. I remember now, playing at ‘Evil People,’ Touter said, “Lets go to the Tit For Tat club and check out Sly.” I said, “Who is Sly?” and he said, “The drummer over there who is wicked.” So I go over there and saw him and I said I always tell my drummer that he must play like that! He (Robbie’s drummer) would get vexed with me! (laughter). I remember that the next day I asked Bunny Lee to book studio time with Sly because everyday I used to do recording, hard everyday, that was it for me, even more than Sly when we got working.

FCJ: How many recording sessions would you typically do in one day at that time?

RS: In the studio it would be continuous with the Aggrovators and other people, you know. The Aggrovators was a Bunny Lee thing, because that was his name. We used to work for everybody – the Upsetters and anybody who wanted a bass player – but it was mainly with the Aggrovators every day. There was a set of us going around and doing the work – me, Earl ‘Chinna’ Smith (Reggae guitar maestro), Santa Davis (Roots Radics drummer) or Leroy ‘Horsemouth’ Wallace (drums). We used to do a lot of work with (drummers) Carly Barrett and Lloyd ‘Thinleg’ Adams, too. There were a lot of different drummers we used to work with at that time.

FCJ: At Randy’s?

RS: At Randy’s, at Treasure Isle, but before at Harry J’s. But basically at Randy’s and Treasure Isle. We used to beat dem thing there. After, when Harry J came in, same treatment. All of this was before I met up with Sly. So the day after meeting Sly, I told Bunny Lee to book some studio time, I met a new drummer and I want to test him. Bunny said, “OK Robbie, anything you say.” So I came to him and said I have a session for him. The first time me and him played in the studio, it got across and everybody there went “Wow! What the..This is wicked!” And I was putting together a band for Peter Tosh. I told Peter about Sly and he said, “Him me want.”

FCJ: This was Tosh’s ‘Equal Rights’ tour as the band ‘Word, Sound, Power’?

RS: Yes. Right after we finished the Equal Rights album, we were getting ready to go out on tour. It was my job to pick the musicians. Peter picked some musicians that he wanted, too. But I said, I want this drummer. So me and Sly have been playing since that first session with Bunny Lee.

FCJ: So how do you and Sly compose together?

RS: We don’t have to say anything, we just work (laughter). Sometimes Sly might come with a song with words and say, “Hey man, I have these words and this little melody.” And we just take it from there, you know. Some of the time, the rhythm will come first, the song can come first if we have the time to write songs easily. I prefer writing to lyrics.

FCJ: Do you have a home studio?

RS: No, no, I don’t take my work home. If I do go home, I want to just chill out. After being in the studio 24-7, when I get that 24 and a half, I keep that half! (laughter).

FCJ: You live in Kingston?

RS: To be right, right now, I live in a suitcase. I live everywhere and live nowhere, it seems to me.

FCJ: Turning to your experiences with non-Reggae music, tell us about working with the Rolling Stones.

RS: It was an experience that you can’t pay for that. You can’t buy that with money, you know.

FCJ: At that point in your career, you were very established. It would seem that they’re approaching you as equals, almost.

RS: Yeah, but you see we were established in the Reggae field. But when we stepped out in a different field with the Rolling Stones, that was the rock and roll field which was new to us. Slightly shocking, like the first time when we played. We were used to playing up close to each other in little clubs. The first time we played with the Rolling Stones, it was in front of like 100,000 people and we said, “Wow!” So you see how it goes on and you start adjusting your style with that, you know. I used to take notes every night. I would watch and learn and ask Mick and Keith questions. Get the answer and they say you probably cant play it 100 percent to Reggae, but try. And we did try it with Black Uhuru and them thing. We were cursing fate at first, but it did work out, you know. And then right in that time, Grace Jones, Joe Cocker, but most of the time with the Rolling Stones, it was to apply stage-work. Which we applied with the Black Uhuru thing as well.

Even with Peter, the first couple of shows were about learning, and from there we expanded. That’s where I started learning about the monitor engineer, the house front engineer. I was the one who got those into place with Peter Tosh. Also focusing on stage movement and things. By the time we reached Black Uhuru, we were tough like rock!

FCJ: Tough!

RS: Yeah! (Laughter) Right? As I said though, applied over the whole full thing, if we work onstage with rock and rollers they would not be able to say we’re there to play just a little Reggae groove. But they would say, these guys (Sly and Robbie) play good music.

FCJ: It opened up stage-craft, the technical side of playing live. Up to that point you guys were studio masters, so this was the other side of it?

RS: Right, yeah. That was the other side of it you know. We learned a lot from everything. I am very observant and wanted to try to expand on what I learned. Sometimes I wanted to expand so fast, but can’t. Even now, sometimes, I cant sleep because I’m thinking of ideas and ways, thinking, ‘we can do this!’ Some little thing will get in my mind and I cant get out of it until I figure it out.

FCJ: You guys are the main attraction now, not strictly playing backline for a singer.

RS: Yeah, well you see, we have an agenda, you know? We’ve been backing people for so long. It’s good you have a singer out front and everything and when you say Sly and Robbie are coming to town, they say ‘Who is the singer?’ This time we say, when Sly and Robbie is coming to town, it’s Sly and Robbie! It’s not about a singer.

FCJ: Well you guys are still at the top. Respect. Thank you very much Robbie.

RS: (Laughter) Yeah man, thank you.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, and Michael O’Connor, our gracious host at the Independent; a venue that has established itself as San Francisco’s premier Rock, Reggae and World Music venue.

Links

Official Sly and Robbie website

Sly and Robbie on Wikipedia

Sly and Robbie on MySpace

Sly and Robbie profile on Allmusic

Sly and Robbie discography on Discogs

Extra Photos!

Nambo and Robbie

Nambo, Bubbler and Eugene Grey

Nambo (trumbone, vocals) and Guillaume “Stepper” Briard (sax, percussion)

The Hunger Site

The Hunger Site

March 30, 2014 at 7:44 pm

Hello?