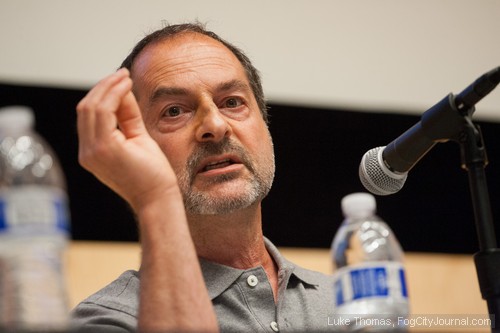

San Francisco Public Defender Jeff Adachi makes introductory remarks to a packed audience attending the 11th annual Justice Summit held at the Civic Center library, 4/23/14. Photos by Luke Thomas.

The San Francisco Public Defender’s 11th annual Justice Summit focused on “things that can cause innocent people to be convicted.”

May 14, 2014

The last days of April delivered a one-two punch of disturbing news on the criminal justice front: release of an academic study suggesting that at least 4.1 percent of death row inmates are innocent, followed the next day by reports of a horrifyingly botched execution in Oklahoma. The successive blows underscore the importance of focusing the public’s attention on the need for systemic reform.

It’s a mission many scholars, activists, practitioners, and even some law enforcement officials take seriously. Here in San Francisco, the city’s top public defender, Jeff Adachi, and the attorneys and staff in his office who labor daily for the cause of indigent defense, attempt to raise awareness in a variety of ways. Chief among their efforts: a yearly forum devoted to criminal justice issues that is free and open to the general public.

The summits “are about areas that need to be reformed and pushing the envelope,” Adachi told FCJ. “We do this to bring people together to talk about solutions for San Francisco and beyond.”

Held each spring in the Koret Auditorium at the San Francisco Public Library, Adachi’s justice summits (see FCJ’s coverage of the 2011 Justice Summit here) have brought a range of topics to the forefront, from the future of the death penalty to the latest techniques in “neuroimaging” as a tool for criminal defense. At these events, attendees have not only heard from experts, they’ve met people who, while experiencing the gravest of injustices, became inspired and effective activists.

The 11th annual Justice Summit attracted a full house of attendees inside the Koret Auditorium, Civic Center library.

This spring’s summit, “The Jury is Out,” featured one such survivor-activist as the keynote speaker: Gloria Killian.

In the early 1980s, Killian was a law school student and a “true believer,” as she put it, in the justice system. Yet, in 1985, she found herself on trial for masterminding a home-invasion robbery that culminated in the brutal murder of an elderly man. Thanks to a secret collaboration between unscrupulous prosecutors and a convicted criminal who had been promised leniency and was willing to lie on the stand to get it, she was convicted and sentenced to life.

“They knew the only proof they had against me was something they contrived,” she said. “But there was real pressure to ‘get somebody.’”

Seventeen years would pass before the United States Court of Appeal for the Ninth Circuit freed her. During that time, she completed her law degree and, to stave off total “destruction of [her] spirit and dignity,” she helped her fellow female inmates “find their voices” and fight their cases. Today, she continues that work as the Executive Director of Action Committee for Women in Prison.

“We need to keep fighting until the system is fair,” she told FCJ. “Nobody should have to go through what I went through. It’s not right.”

Author Gloria Killian.

Georgia Killian was presented with flowers and a commendation from the San Francisco Public Defender’s office.

(For a more detailed account of Killian’s story, see CNN’s March 23, 2014 edition of “Death Row Stories” or the book she co-authored, “Full Circle: A True Story of Murder, Lies and Vindication”).

The main part of the 2014 Justice Summit consisted of three panel discussions. The first focused on the problematic role that human memory can play in criminal adjudication. The second addressed the impact of having a mother or father (or both) behind bars, as well as the experience of being the locked-up parent. The third dealt with issues surrounding plea bargaining.

Panel I: “Beyond Woody Allen: Can We Trust Our Memories?”

On February 1, the New York Times published Dylan Farrow’s “Open Letter,” in which the adopted daughter of actress Mia Farrow and filmmaker Woody Allen recounted the alleged sexual abuse she suffered at the hands of Allen when she was a child. Farrow’s piece, which marked the first time she publicly shared the story as an adult, brought the allegations against Allen back to the forefront some twenty years after her mother had made them. The letter also renewed the debate over the reliability of childhood sexual abuse memories and inspired the title of the first panel.

In her introductory remarks, moderator Sangeeta Sinha, a Deputy Public Defender in Adachi’s office, noted that cognitive scientists now generally agree that human memory is “malleable, susceptible to distortion, contamination and other forces” that can make it inaccurate.

San Francisco deputy public defender Sangeeta Sinha.

And yet, for better or worse, “every case and every trial is about memory,” as panelist Douglas Horngrad pointed out. His remark was essentially an acknowledgement of the major role that witness recollection plays throughout any criminal proceeding – from the filing of charges to the eventual determination of guilt or innocence.

Horngrad defended George Franklin, who, in 1990, was convicted for molesting and killing an 8-year-old girl some twenty years earlier. The evidence against Franklin consisted solely of his adult daughter’s sudden recollection of having seen him commit the crimes when she was a child. Ultimately, a federal court overturned his conviction – in part because the daughter had admitted on the stand that her “memory” was drawn out through hypnosis. According to Horngrad, the gist of the judge’s decision was that in a case of “recovered” or “repressed” memory, there has to be other, corroborating evidence.

Attorney Douglas Horngrad.

Panelist Melina Uncapher, a neuroscientist and memory expert at Stanford University’s Memory Laboratory, said that scientists have found “no real evidence of truly ‘repressed’ memory.”

She suggested that a so-called ‘repressed’ or ‘recovered’ memory is simply one that a person has not accessed in a long time. “There are tons of memories in your brain that once you turn your attention to, you can remember,” she said.

Neuroscientist Melina Uncapher.

Panelist Jim Hammer, a legal analyst who formerly headed the homicide division of the San Francisco District Attorney’s office, cautioned prosecutors and investigators to “look very closely” at evidence based on witness recollection, to “dig” for the truth, and to “treat a situation where someone `forgot’ [and then suddenly remembered] a memory with special attention.”

“Our worst nightmare is putting an innocent person in jail,” he said.

Attorney Jim Hammer.

Uncapher also said that memories can be implanted.

(Some Woody Allen defenders have accused Mia Farrow of implanting the memory of abuse in her child’s mind during the couple’s bitter, and well-publicized break-up in the early 1990s).

“That can and does happen in many different ways,” Uncapher said. She mentioned as an example that “people can be told of other people’s memories and take them on as their own.”

Earlier, Uncapher explained that the fallibility of human memory also has to do with its “constructive” nature.

From brain scans, scientists can see that “when we retrieve a memory, we have to go into different parts of the brain to bring [it] back,” she said. In so doing, the brain can easily fuse unrelated information from various “storage files” to create an impression of an occurrence. The retrieval process, she said, is “very prone to error,” and the resulting memory “can be very distorted.”

Studies have disproved the commonly-held belief that the more details a person can remember, or the more confident he or she is in the accuracy of the recollection, the more likely the memory is accurate.

“That is not the case,” she said.

Panelist Joey Piscatelli, the Northern California director of the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, offered a different perspective.

Piscatelli said that “throwing a blanket of ‘false memory’” on recollections of abuse that surface years after the abuse occurred discourages victims from coming forward.

“There’s no epidemic of false memory,” he said. “What there is, is an epidemic of sexual abuse, and especially child sexual abuse.”

He said he counsels abuse victims faced with testifying in court to “recall exactly as it happened” and “don’t add or subtract.”

“We shouldn’t label everyone who comes forward with a memory as a liar.”

Activist Joey Piscatelli.

Panel II: Children of Incarcerated Parents

In the United States today, some three million children have at least one parent who is in prison, Adachi said during introductory remarks.

The experience has become so commonplace that the children’s television show “Sesame Street” recently introduced a puppet-character whose father is in jail, noted moderator Nicole Harris, a re-entry social worker in the Children of Incarcerated Parents Program in Adachi’s office.

Having a parent in prison profoundly affects a child, the panelists agreed.

Attorney Chesa Boudin said that children in this situation often “internalize” the stigma of incarceration and feel guilty.

Boudin was a toddler when his parents, Kathy Boudin and David Gilbert, members of the left-wing Weather Underground, went to prison for their involvement in the politically motivated 1981 robbery of a Brinks armored truck. A security guard and two police officers were shot and killed during the incident.

“I remember having thoughts like, `If I had been more lovable [this wouldn’t have happened]’ or, `If only I could have told them not to go,’” Chesa Boudin said. He also said that during his youth he felt anger, that he “had fights and outbursts up until high school.”

Even so, Boudin went on to earn two masters degrees from Oxford University, and a law degree from Yale University. He has translated, edited and authored several books, including his latest, “Gringo: A Coming of Age in Latin America.” Boudin worked in the misdemeanor unit of the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office in 2012-13 and currently clerks for Judge Charles Breyer of the United States District Court, Northern District of California.

Attorney Chesa Boudin.

Panelist Ameerah Tubby said that after her mother went to jail, for a period of time “she wasn’t communicative” with people, because she “wasn’t communicative with [her mother].” “Because of that I acted out in many ways,” she said.

Tubby, however, became involved in Project WHAT!, an organization for youths with incarcerated parents. “We write our stories, and we support each other,” said Tubby, whose father is also in prison.

Ameerah Tubby.

Boudin and Tubby agreed that instability, that is, “being bounced around” from home to home is one of the most difficult challenges facing a child who has lost both parents to the system.

Boudin was fortunate. Not long after his parents started serving their sentences, their close friends William Ayers, co-founder of the Weather Underground, and his wife, Bernadine Dohrn, adopted him as their own.

Moderator Harris and panelist Chesa Boudin said that the great distances that typically lie between the places where the children live and the facilities where their parents are imprisoned is another major issue.

“Most [children] live one hundred or more miles away,” Boudin said.

Kathy Boudin (Chesa’s mother), and Daisy Wagaman (Bram) provided the parents’ perspective.

Boudin said it was difficult to hear her young son refer to his adoptive mother as “mom,” while he called her, “Kathy.”

“Chesa explained to me that `mom’ is the word a child calls out when he needs help,” she said. “Giving up that role was hard… [but] I knew I couldn’t be ‘mom.’”

Boudin said she spent time crocheting, trying to make stuffed animals for Chesa.

“[Literally] in that thread, I was trying to reestablish that connection,” she said.

Kathy Boudin.

During the 22 years she spent behind bars, Kathy Boudin founded a number of prison support and inmate-education groups, earned a Masters Degree in Adult Education, wrote academic articles, co-authored “The Foster Care Handbook for Incarcerated Parents,” co-edited “Parenting from inside/out: Voices of mothers in prison,” and published poetry, for which she won an International PEN prize in 1999. She is now an adjunct professor at Columbia University’s School of Social Work and the director of Criminal Justice Initiative: Supporting Children, Families and Communities. Her husband is still in prison serving a 70-year sentence.

Daisy Wagaman (Bram) agreed that it can be devastating for an imprisoned mother to hear her child refer to another woman as his maternal caregiver.

“Because my sons have spent so much time in foster care, there’s another woman who the little ones call ‘Mama,’” she said, as she choked back tears.

Daisy Wagaman.

Wagaman’s three sons were taken from her in 2011 as a result of her arrest on marijuana-growing charges. Two of her boys were still nursing at the point when police burst through the door to her home and tore the youngest from her arms.

Today, her children are with her from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday, she said. But the time when they are not in her care is still heart-wrenching for her. She has become an advocate for families who are experiencing forced separations due to the parents’ entanglement in the criminal justice system.

“It’s really hard to maintain the rights you assume are inherent in giving birth when you’re in jail,” she said. “But the only decision you can make is what to do with the hand you were dealt.”

Panel III: The Death of the Jury Trial

For the final discussion of the day, the focus turned to another aspect of the criminal justice system that can be viewed as falling under the rubric of “things that can cause innocent people to be convicted,” as Adachi put it.

The first panel had addressed a frequent contributor to erroneous outcomes in criminal proceedings: the system’s heavy reliance on human memory, despite its fallibility. In her keynote address, Killian had mentioned others, such as false confessions (often resulting from improper police interrogation or overt pressure) and shoddy methods of scientific inquiry. Her own story stands as a glaring example of wrongful conviction due to egregious prosecutor misconduct.

Plea bargaining is the process by which a defendant gives up the right to trial and pleads guilty or “no contest” to a charge, in exchange for some sort of concession from the prosecutor, usually a more lenient sentence or the dropping of other charges.

“Copping a plea” is perhaps the most commonplace element of the system. According to Adachi, it is estimated that more than 98 percent of criminal cases are resolved in this manner.

In his welcoming remarks, Adachi referred to plea bargaining as a “scourge” of the system. In the afternoon, right before he introduced the panelists who would speak on the subject, he cited comments made by Federal District Court Judge Jed Rakoff during a lecture he gave last month at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law.

“Plea bargains have led many innocent people to take a deal,” Adachi quoted Rakoff as saying. “People accused of crimes are often offered five years by prosecutors or face 20 to 30 if they go to trial. …The prosecutor has the information, he has all the chips … and the defense lawyer has very, very little to work with. So it’s a system of prosecutor power and prosecutor discretion.

“We have hundreds, or thousands, or even tens of thousands of innocent people who are in prison, right now, for crimes they never committed because they were coerced into pleading guilty.”

(Rakoff’s remarks were not the only source of heightened interest in plea bargaining last month. California Lawyer magazine devoted the cover of its April edition to the topic. See “Pleading for Justice,” by freelance writer and attorney Michael Estrin).

Panelist George Fisher, a Stanford Law professor and former prosecutor, said that when a prosecutor threatens a defendant “with an inordinately high sentence,” should he go to trial and lose, and then offers “a very low sentence,” if he agrees to plead guilty or “no contest,” the prosecutor is engaging in a form of coercion.

“That’s certainly not something we should applaud,” he said.

(A “no contest plea,” where the defendant does not admit guilt, counts as a conviction and is treated the same as a guilty plea in sentencing).

Fisher is the author of “Plea Bargaining’s Triumph: A History of Plea Bargaining in America.” In the book, Fisher attributes the rise of the plea deal to the increase in caseloads and overwhelmed courts and judges.

Stanford Law professor George Fisher.

Adachi said that the high cost of bail as well as “extreme sentencing schemes” are frequent factors behind an innocent people agreeing to plead guilty.

Panelists Brendon Woods, who heads the Alameda County Public Defender’s office and Nicole Solis, a Deputy Public Defender in Adachi’s office, said that in their experiences, innocent defendants sometimes do agree to plead guilty to crimes they did not commit.

“Do innocent people plead guilty?” Woods asked. “Yes, they do.”

Even when an investigation might uncover facts showing the defendant’s innocence, he or she might still be unwilling to risk losing at trial and then having to live behind bars for a much longer time.

“I might think, `I’ve got a wife. I’ve got kids.’ I might want to see my daughter get married,” Woods mused. “Would I take the deal? Yes, yes I would.”

Alameda County Public Defender Brendon Woods.

Before accepting a plea of guilty, the judge is required to ask whether a factual basis exists for the plea, as well as make sure the defendant understands the rights he is giving up. While a judge has the power to reject a plea deal, the authority is exercised infrequently.

Panelist Quentin Kopp, the former San Francisco supervisor and state senator who is also a retired Superior Court judge, said he did not agree with the assertion that “innocent people are being confined as a result of forced plea bargaining.”

“In the 10 or so counties where I served as a judge or sat after retirement, I just can’t imagine [such] scenarios,” he said. “If a judge believes that a defendant involved in a negotiation to plead guilty or no contest is not guilty, that judge has an obligation to refuse a plea.”

Kopp pointed out that “many conservative legislators think plea bargaining is evil because it results in less severe sentences that what could be imposed.”

Former California Senator and Superior Court Judge Quentin Kopp.

Adachi and all of the panelists agreed on one point – that a defendant’s willingness to go to trial often comes down to how much faith she has in her attorney, and the attorney’s level of aggressiveness and training.

Panelist Alexandra Berliner, a criminal and juvenile justice activist, said that at one point in her life, she agreed to plead guilty to an assault-related charge, even though she “wasn’t even there at the scene.”

“My attorney said it would be better to take the deal,” she said. Berliner said that when her boyfriend was faced with a similar situation, he agreed to do the same.

Alexandra Berliner.

San Francisco Deputy Public Defender Nicole Solis.

Adachi brought out that Berliner and her partner had not felt that they had attorneys who could “strongly present” their stories to the court.

Woods said that when his office hires attorneys, they look for those who “want to fight,” who “want to go to trial.”

“It’s important to give them training, a lower caseload, and more time to investigate,” he said.

As Adachi told FCJ following the summit, “It really comes down to hard work and training.”

The Hunger Site

The Hunger Site

No Comments

Comments for Criminal Injustice are now closed.